Please accompany me on a journey through time and space in search of the sense and nonsense of pandemics and epidemics

Same Symptoms include chills, nausea, loss of appetite, headaches and muscle pain.

1. The origins of vaccination

A REPORT ON ANTIMENINGITIS VACCINATION AND OBSERVATIONS ON AGGLUTININS IN THE BLOOD OF CHRONIC MENINGOCOCCUS CARRIERS.

BY FREDERICK L. GATES,M. D.

First Lieutenant, Medical Corps, U. S. Army.

(From the Base Hospital, Fort Riley, Kansas, and The RockefellerInstitute ./or Medical Research,New York.)

PLATES 47 AND 48.

(Received for publication, July 20, 1918.)

Following an outbreak of epidemic meningitis at Camp Funston, Kansas, in October and November, 1917, a series of antimeningitis vaccinations was undertaken on volunteer subjects from the camp. Major E. H. Schorer, Chief of the Laboratory Section at the adjacent Base Hospital at Fort Riley, offered every facility at his command and cooperated in the laboratory work connected with the vaccina- tions. In the camp, under the direction of the Division Surgeon, Lieutenant Colonel J. L. Shepard, a preliminary series of vaccinations on a relatively small number of volunteers served to determine the appropriate doses and the resultant local and general reactions. Fol- lowing this series, the vaccine was offeredby the Division Surgeon to the camp at large, and „given by the regimental surgeons to all who wished to take it.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2126288/pdf/449.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2126288/

“Frederick Lamont Gates injected the USA army on behalf of ‘the Rockefeller Foundation’ at Fort Riley!! They were injected with an experimental ‘bacterial meningitis’ #Vaccine derived from horses!!”

https://www.bitchute.com/embed/Bkx7aNSOS0c9/?feature=oembed#?secret=Vx9s1qCNnM

Denis has a PhD in Physics (1984, University of Toronto), is a former tenured Full Professor (University of Ottawa), and has published over one hundred articles in leading science journals. Denis’ reports and articles can be found here:

2. The origins of vaccination

The procedure of ‘variolation’, by which pus is taken from a smallpox blister and introduced into a scratch in the skin of an uninfected person to confer protection, was in practice in Asia centuries before the first reports of inoculation in Europe. Read MoreBy Alexandra Flemming

Edward Jenner (1749–1823), a physician from Gloucestershire in England, is widely regarded as the ‘father of vaccination’ (Milestone 2). However, the origins of vaccination lie further back in time and also further afield. In fact, at the time Jenner reported his famous story about inoculating young James Phipps with cowpox and then demonstrating immunity to smallpox, the procedure of ‘variolation’ (referred to then as ‘inoculation’), by which pus is taken from a smallpox blister and introduced into a scratch in the skin of an uninfected person to confer protection, was already well established.

Variolation had been popularized in Europe by the writer and poet Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, best known for her ‘letters from the Ottoman Empire’. As wife of the British ambassador to Turkey, she had first witnessed variolation in Constantinople in 1717, which she mentioned in her famous ‘letter to a friend’. The following year, her son was variolated in Turkey, and her daughter received variolation in England in 1721. The procedure was initially met with much resistance — so much so that the first experimental variolation in England (including subsequent smallpox challenge) was carried out on condemned prisoners, who were promised freedom if they survived (they did). Nevertheless, the procedure was not without danger and subsequent prominent English variolators devised different techniques (often kept secret) to improve variolation, before it was replaced by the much safer cowpox ‘vaccination’ as described by Jenner.

But how did variolation emerge in the Ottoman Empire? It turns out that at the time of Lady Montagu’s letter to her friend, variolation, or rather inoculation, was practised in a number of different places around the world. In 1714, Dr Emmanuel Timmonius, resident in Constantinople, had described the procedure of inoculation in a letter that was eventually published by the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (London). He claimed that “the Circassians, Georgians, and other Asiatics” had introduced this practice “among the Turks and others at Constantinople”. His letter triggered a reply from Cotton Maher, a minister in Boston, USA, who reported that his servant Onesimus had undergone the procedure as a child in what is now southern Liberia, Africa. Moreover, two Welsh doctors, Perrot Williams and Richard Wright, reported that inoculation was well known in Wales and had been practised there since at least 1600.

Patrick Russell, an English doctor living in Aleppo (then part of the Ottoman Empire), described his investigations into the origins of inoculation in a letter written in 1786. He had sought the help of historians and doctors, who agreed that the practice was very old but was completely missing from written records. Nevertheless, it appears that at the time, inoculation was practised independently in several parts of Europe, Africa and Asia. The use of the needle (and often pinpricks in a circular pattern) was a common feature, but some places had other techniques: for example, in Scotland, smallpox-contaminated wool (a ‘pocky thread’) was wrapped around a child’s wrist, and in other places, smallpox scabs were placed into the hand of a child in order to confer protection. Despite the different techniques used, the procedure was referred to by the same name — ‘buying the pocks’ — which implies that inoculation may have had a single origin.

Two places in particular have been suggested as the original ‘birthplace of inoculation’: India and China. In China, written accounts of the practice of ‘insufflation’ (blowing smallpox material into the nose) date to the mid-1500s. However, there are claims that inoculation was invented around 1000 ad by a Taoist or Buddhist monk or nun and practised as a mixture of medicine, magic and spells, covered by a taboo, so it was never written down.

Meanwhile, in India, 18th century accounts of the practice of inoculation (using a needle) trace it back to Bengal, where it had apparently been used for many hundreds of years. There are also claims that inoculation had in fact been practised in India for thousands of years and is described in ancient Sanscrit texts, although this has been contested.

Given the similarities between inoculation as practised in India and in the Ottoman Empire, it may be more likely that variolation, as described by Lady Montagu, had its roots in India, and it may have emerged in China independently. However, given that the ancient accounts of inoculation in India are contested, it is also possible that the procedure was invented in the Ottoman Empire and spread along the trade routes to Africa and the Middle East to reach India.

Regardless of geographical origin, the story of inoculation eventually led to one of the greatest medical achievements of humankind: the eradication of smallpox in 1980. And of course, it inspired the development of vaccines for many more infectious diseases, turning this planet into a much safer place.

Unbelievable! What a great magical bullshit story!!!

Boylston, A. The origins of inoculation. J. R. Soc. Med. 105, 309–313 (2012).

The first live attenuated vaccines

Awareness of Edward Jenner’s pioneering studies of smallpox vaccination (Milestone 2) led Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) to propose that vaccines could be found for all virulent diseases.

Pasteur began to study chicken cholera in 1877 and by the following year had succeeded in culturing the causative organism, Pasteurella multocida. In 1879, Pasteur discovered by chance that cultures of this bacterium gradually lost their virulence over time. Before leaving to go on a holiday, Pasteur had instructed an assistant to inject the latest batch of chickens with fresh cultures of P. multocida. The assistant forgot to do this, however, and then himself went on holiday. On his return, Pasteur’s assistant inoculated the chickens with the cultures, which by this time had been left in the laboratory for a month, stoppered only with a cotton-wool plug. The inoculated chickens developed mild symptoms but recovered fully.

Another scientist might have concluded that the cultures had (mostly) died, but Pasteur was intrigued. He injected the recovered chickens with freshly cultured cholera bacteria. When the birds remained healthy, Pasteur reasoned that exposure to oxygen had caused the loss of virulence. He found that sealed bacterial cultures maintained their virulence, whereas those exposed to air for differing periods of time before inoculation showed a predictable decline in virulence. He named this progressive loss of virulence ‘attenuation’, a term still in use today.

Pasteur, along with Charles Chamberland and Emile Roux, went on to develop a live attenuated vaccine for anthrax. Unlike cultures of the chicken cholera bacterium, Bacillus anthracis cultures exposed to air readily formed spores that remained highly virulent irrespective of culture duration; indeed, Pasteur reported that anthrax spores isolated from soil where animals that died of anthrax had been buried 12 years previously remained as virulent as fresh cultures. However, Pasteur discovered that anthrax cultures would grow readily at a temperature of 42–43 °C but were then unable to form spores. These non-sporulating cultures could be maintained at 42–43 °C for 4–6 weeks but exhibited a marked decline in virulence over this period when inoculated into animals.

Accordingly, in public experiments at Pouilly-le-Fort, France, conducted under a media spotlight reminiscent of that on today’s COVID-19 treatment trials, 24 sheep, 1 goat and 6 cows were inoculated twice with Pasteur’s anthrax vaccine, on 5 and 17 May 1881. A control group of 24 sheep, 1 goat and 4 cows remained unvaccinated. On 31 May all the animals were inoculated with freshly isolated anthrax bacilli, and the results were examined on 2 June. All vaccinated animals remained healthy. The unvaccinated sheep and goats had all died by the end of the day, and all the unvaccinated cows were showing anthrax symptoms. Chamberland’s private laboratory notebooks, however, showed that the anthrax vaccine used in these public experiments had actually been attenuated by potassium dichromate, using a process similar to that developed by Pasteur’s competitor, Jean Joseph Henri Toussaint.

In 1881, Victor Galtier (who had already demonstrated transmission of rabies from dogs to rabbits) reported that sheep injected with saliva from rabid dogs were protected from subsequent inoculations. These surprising observations piqued Pasteur’s interest and he went on to develop the first live attenuated rabies vaccine.

Despite failing to culture the rabies-causing organism outside animal hosts or to view it under a microscope (because, unknown to Pasteur, rabies is caused by a virus rather than a bacterium), Pasteur discovered that the virulence of his rabies stocks, maintained by serial intracranial passage in dogs, decreased when the infected material was injected into different species. Starting with a highly virulent rabies strain serially passaged many times in rabbits, Pasteur air-dried sections of infected rabbit spinal cord to weaken the virus through oxygen exposure, as explained in Pasteur’s 26 October 1885 report to the French Academy of Science. All 50 dogs vaccinated with this material by Pasteur were successfully protected from rabies infection, although we now understand attenuation to result from viral passage through dissimilar species, rather than air exposure.

Up to this point, however, Pasteur had no proof that his vaccines, a term coined by Pasteur to honour Jenner’s work, would be effective in humans. Reluctantly — as Pasteur was not a licensed physician and could have been prosecuted for doing so — on 6 July 1885, Pasteur used his rabies vaccine, in the presence of two local doctors, to treat 9-year-old Joseph Meister, who had been severely bitten by a neighbour’s rabid dog. Joseph Meister received a total of 13 inoculations over a period of 11 days, and survived in good health. Pasteur’s reluctance might also be accounted for by posthumous analysis of his laboratory notebooks, which revealed that Pasteur had vaccinated two other individuals before Meister; one remained well but might not actually have been exposed, and the other developed rabies and died.

By the end of 1885, several more desperate rabies-exposed people had travelled to Pasteur’s laboratory to be vaccinated. During 1886, Pasteur treated 350 people with his rabies vaccine, of whom only one developed rabies. The startling success of these vaccines led directly to the founding of the first Pasteur Institute in 1888.

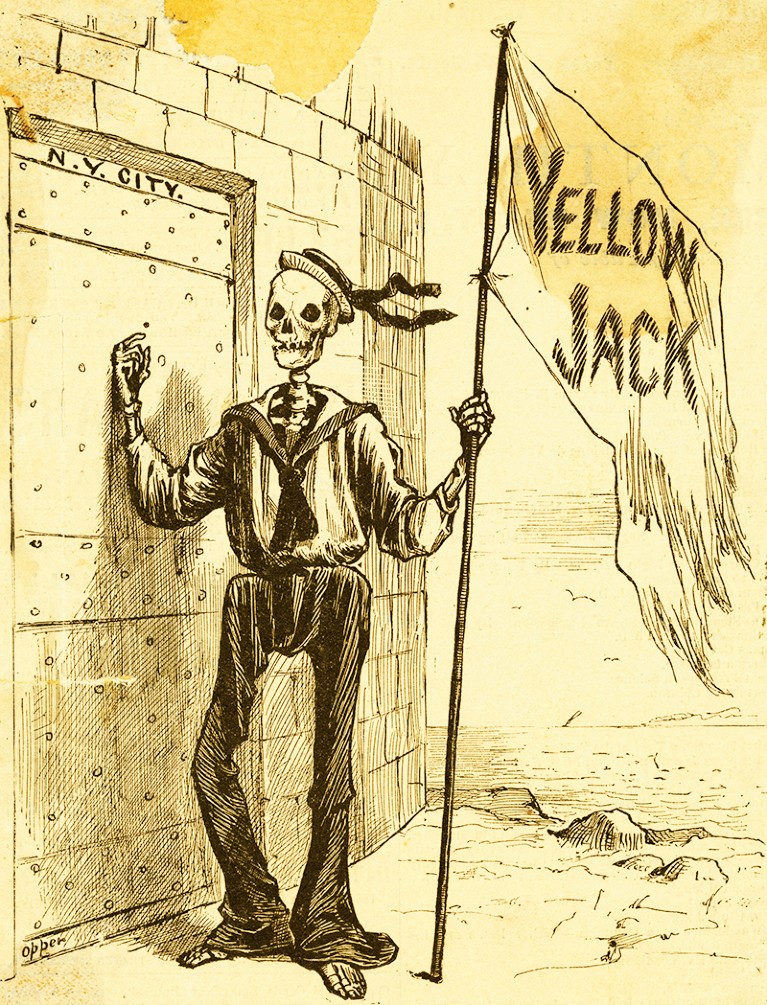

Developing the 17D yellow fever vaccine

By the end of the 19th century, the feared yellow fever (often known as ‘yellow jack’ owing to the yellow quarantine flag on infected ships) had reached South America, the USA and Europe. Caused by a zoonotic flavivirus spread by an infected female mosquito, mostly Aedes aegypti, the slave trade and global markets had helped to spread the disease around the world. Yellow fever is now endemic in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa and tropical South America, with the vast majority of cases occurring on the African subcontinent.

Yellow fever symptoms include chills, nausea, loss of appetite, headaches and muscle pain.

Sounds familiar?

In most people, these symptoms improve in around 5 days; however, for around 15% of cases, the fever returns with abdominal pain, jaundice and liver damage. Up to half of these individuals with severe disease will die.

Unsuccessful attempts to create a vaccine for yellow fever — including vaccines against a spirochaete or other bacteria — date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before the causative agent of yellow fever had been identified. This is where South African virologist Max Theiler enters the story. Theiler started his work on yellow fever at the Harvard University School of Tropical Medicine in the USA. He and his colleagues confirmed that the disease was viral, and by 1928 they had shown that the same virus was responsible for both the African and South American pools of disease.

Researchers at the Rockefeller Foundation in the USA isolated the causative virus from the blood of a Ghanaian man called Asibi, and a team from the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, Senegal isolated the ‘French strain’ of the virus from a Lebanese man, Francoise Mayali. Once in the lab, these researchers found that serum from patients with yellow fever protected monkeys from infection but that killed virus was not effective at inducing immunity.

Sounds familiar?

In 1930, Theiler moved to the Rockefeller Foundation in New York, where he worked to reduce the pathogenicity of the virus so that it could be used as a vaccine that triggered immunity but did not cause systemic damage. He showed that repeated passage in mouse brain cultures reduced the effect of the virus on most organs, but potentially increased its impact on the central nervous system, which could cause encephalitis.

In 1931, after around 100 passages in mouse brain, the Rockefeller Institute tested a modified French strain as a vaccine, in combination with immune serum from recovered patients to reduce the risk of encephalitis. But the risk of neurotoxicity was still there and the large quantities of serum that were required made it hard to scale up its use. So, another approach was needed.

And now it’s getting really disgusting!!!

In a sequence of three publications in the Journal of Experimental Medicine in 1937, Max Theiler and Hugh Smith described the development of a live attenuated yellow fever vaccine strain using tissue from embryonated chicken eggs. The researchers focused on the Asibi strain, from which strain 17D was isolated after 176 passages initially in mouse embryonic tissue and monkey serum, and later in minced whole chick embryo, then in chick embryo from which the brain and spinal cord had been removed. 17D had lost neurotropism, viscerotropism and mosquito competence, but it still had the potential to trigger an immune response.

Ernest Goodpasture, a US pathologist and medic, should be given due credit for paving the way for this stage of the research. Working in the early 1930s, he and his fellow researchers were the first to reproducibly grow pure viruses in culture by infecting fertilized chicken eggs. Prior to this, viruses could only be studied in costly animal models or in tissue cultures that were prone to contamination by bacteria because antibiotics were not yet available.

The next step for Theiler and his team was to see whether a 17D vaccine prepared from infected whole chick embryos was safe and effective for human use without the addition of human serum, the bottleneck for Theiler’s previous vaccine. In a study in rhesus monkeys, the vaccine triggered antibodies in all monkeys by 14 days and immunity to infection after a week. There were few adverse effects in the monkeys, so the researchers vaccinated four people who were already immune and eight people with no immunity. All developed antibody responses, and adverse effects were limited to mild fever, headache and backache. (But this are exactly the symptoms that there want to preserve?!) The positive results of this preliminary trial led to further larger studies.

The 17D vaccine received licensing approval in 1938, with more than 850 million doses having been distributed since. The vaccine is well tolerated, up to 100% effective and affordable, and it can provide lifelong protection with a single vaccination. Serious side effects are rare. In 1951, Theiler was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “discoveries concerning yellow fever and how to combat it”, the first and only time that the prize has been awarded for a vaccine.

Human dignity in the Nazi era: implications for contemporary bioethics

The search for an answer must delve into the underlying beliefs commonly held at that time. This investigation is crucial because if those beliefs prevail again we must wonder whether such unconscionable behaviour will likely follow in their path. The origins of the Nazi atrocities do not lie in concentration camps set up by a totalitarian dictatorship. They are rooted in beliefs promoted by particular social philosophies and practices that began in hospitals.

BMC Med Ethics. 2006; 7: 2. Published online 2006 Mar 14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-7-2

PMCID: PMC1484488PMID: 16536874

Human Cell Strains in Vaccine Development

Language Selector Englishcurrent language

Animals have been used in the industrialized production of human vaccines since vaccine farms were established to harvest cowpox virus from calves in the late 1800s. From that point, and through the first half of the 20th Century, most vaccines would continue to be developed with the use of animals, either by growing pathogens in live animals or by using animal cells.

Although many vaccines and anti-toxin products were successfully developed this way, using animals in vaccine development – particularly live animals – is not ideal. Research animals are costly and require extensive monitoring, both to maintain their health and to ensure the continued viability of the research. They may be carrying other bacteria or viruses that could contaminate the eventual vaccine, as with polio vaccines from the mid 20th century that were made with monkey cells and eventually found to contain a monkey virus called SV40, or Simian Virus 40. (Fortunately, the virus was not found to be harmful to humans.) Moreover, some pathogens, such as the chickenpox virus, simply do not grow well in animal cells.

Even when vaccine development is done using animal products and not live animals – such as growing influenza vaccine viruses in chicken eggs – development can be hindered or even halted if the availability of the animal products drops. If an illness were to strike the egg-producing chickens, for example, they might produce too few eggs to be used in the development of seasonal flu vaccine, leading to a serious vaccine shortage. (It’s a common misconception that influenza vaccines could be produced more quickly if grown in cell cultures compared to using embryonated chicken eggs. In fact, growing the vaccine viruses in cell cultures would take about the same amount of time. However, cell cultures do not have the same potential availability issues as chicken eggs.)

For these and other reasons, using cell culture techniques to produce vaccine viruses in human cell strains is a significant advance in vaccine development.

How Cell Cultures Work

Cell cultures involve growing cells in a culture vessel. A primary cell culture consists of cells taken directly from living tissue and never sub-cultivated, and may contain multiple types of cells such as fibroblasts, epithelial, and endothelial cells.

A cell strain is a cell culture that contains only one type of cell in which the cells are normal and have a finite capacity to replicate. Cell strains can be made by taking subcultures from an original, primary culture until only one type remains. Primary cultures can be manipulated in many different ways in order to isolate a single type of cell; spinning the culture in a centrifuge can separate large cells from small ones, for example. An immortalized cell line is a cell culture of a single type of cell that can reproduce indefinitely. Normally, cells are subject to the Hayflick Limit, a rule named for cell biologist Leonard Hayflick, PhD. Hayflick determined that a population of normal human cells will reproduce only a finite number of times before they cease to reproduce. However some cells in culture have undergone a mutation, or they have been manipulated in the laboratory, so that they reproduce indefinitely. One example of an immortalized cell line is the so-called HeLa cell line, started from cervical cancer cells taken in the 1950s from a woman named Henrietta Lacks. Cell lines are not used to produce vaccine viruses.

Researchers can grow human pathogens like viruses in cell strains to attenuate them – that is, to weaken them. One way viruses are adapted for use in vaccines is to alter them so that they are no longer able to grow well in the human body. This may be done, for example, by repeatedly growing the virus in a human cell strain kept at a lower temperature than normal body temperature. In order to keep replicating, the virus adapts to become better at growing at the lower temperature, thus losing its original ability to grow well and cause disease at normal body temperatures. Later, when it’s used in a vaccine and injected into a living human body at normal temperature, it still provokes an immune response but can’t replicate enough to cause illness.

Vaccines Developed Using Human Cell Strains

The first licensed vaccine made with the use of a human cell strain was the adenovirus vaccine used by the military in the late 1960s. Later, other vaccines were developed in human cell strains, most notably the rubella vaccine developed by Stanley Plotkin, MD, at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia.

In 1941, Australian ophthalmologist Norman Gregg first realized that congenital cataracts in babies were the result of their mothers being infected with rubella during pregnancy. Along with cataracts, it was eventually determined that congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) could also cause deafness, heart disease, encephalitis, mental retardation, and pneumonia, among many other conditions. At the height of a rubella epidemic that began in Europe and spread to the United States in the mid-1960s, Plotkin calculated that 1% of all births at Philadelphia General Hospital were affected by congenital rubella syndrome. In some cases, women who were infected with rubella while pregnant terminated their pregnancies due to the serious risks from CRS.

Following one such abortion, the fetus was sent to Plotkin at the laboratory he had devoted to rubella research. Testing the kidney of the fetus, Plotkin found and isolated the rubella virus. Separately, Leonard Hayflick (also working at the Wistar Institute at that time) developed a cell strain called WI-38 using lung cells from an aborted fetus. Hayflick found that many viruses, including rubella, grew well in the WI-38, and he showed that it proved to be free of contaminants and safe to use for human vaccines.

Plotkin grew the rubella virus he had isolated in WI-38 cells kept at 86°F (30°C), so that it eventually grew very poorly at normal body temperature. (He chose the low temperature approach following previous experiences with attenuating poliovirus.) After the virus had been grown through the cells 25 times at the lower temperature, it was no longer able to replicate enough to cause illness in a living person, but was still able to provoke a protective immune response. The rubella vaccine developed with WI-38 is still used throughout much of the world today as part of the combined MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine.

Ethical Issues with Human Cell Cultures

Although it has now been used in the United States for more than 30 years, Plotkin’s rubella vaccine was initially ignored by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in favor of rubella vaccines developed using duck embryo cells and dog kidney cells. In the late 1960s, there was concern in the country that a vaccine developed using human cells could be contaminated with other pathogens, though this concern was not supported by documented evidence. This is interesting in light of the discovery earlier in the decade that polio vaccines developed using primary monkey kidney cells were contaminated with simian viruses: this was one of the reasons researchers began using the normal human cell strain WI-38 in the first place. According to Hayflick, however, the main reason for using WI-38 was the fact that it could be stored in liquid nitrogen, reconstituted, and tested thoroughly before use for contaminating viruses. (None has ever been found in WI-38.) Primary monkey kidney cells could not be frozen and then reconstituted for testing as this would violate the concept of primary cells–originally the only class of cells allowed by the FDA to produce human virus vaccines.

After testing, Plotkin’s vaccine was first licensed in Europe in 1970 and was widely used there with a strong safety profile and high efficacy. In light of that data, and of larger side effect profiles with the other two rubella vaccines, it was licensed in the United States in 1979 and replaced the rubella vaccine component that had previously been used for Merck’s MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) combination vaccine. In 2005 the CDC declared rubella eliminated from the United States, though the threat from imported cases remains. The World Health Organization declared the Americas free from rubella in 2015.

Groups that object to abortion have raised ethical questions about Plotkin’s rubella vaccine (and other vaccines developed with similar human cell strains) over the years.

Because of its position on abortion, some members of the Catholic Church asked for its moral guidance on the use of vaccines developed using cell strains started with human fetal cells. This includes the vaccine against rubella as well as those against chickenpox and hepatitis A, and some other vaccines. The official position according to the National Catholic Bioethics Center is that individuals should, when possible, use vaccines not developed with the use of these human cell strains. However, in the case where the only vaccine available against a particular disease was developed using this approach, the NCBC notes:

One is morally free to use the vaccine regardless of its historical association with abortion. The reason is that the risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concern about the origins of the vaccine. This is especially important for parents, who have a moral obligation to protect the life and health of their children and those around them.

The NCBC does note that Catholics should encourage pharmaceutical companies to develop future vaccines without the use of these cell strains. To address concerns about fetal cells remaining as actual ingredients of the vaccines, however, they specifically note that fetal cells were used only to begin the cell strains that were used in the preparation of the vaccine virus:

Descendant cells are the medium in which these vaccines are prepared. The cell lines under consideration were begun using cells taken from one or more fetuses aborted almost 40 years ago. Since that time the cell lines have grown independently. It is important to note that descendant cells are not the cells of the aborted child. They never, themselves, formed a part of the victim’s body.

In total only two fetuses, both obtained from abortions done by maternal choice, have given rise to the human cell strains used in vaccine development. Neither abortion was performed for the purpose of vaccine development.

Current Vaccines Developed Using Human Cell Strains

Two main human cell strains have been used to develop currently available vaccines, in each case with the original fetal cells in question obtained in the 1960s. The WI-38 cell strain was developed in 1962 in the United States, and the MRC-5 cell strain (also started with fetal lung cells) was developed, using Hayflick’s technology, in 1970 at the Medical Research Center in the United Kingdom. It should be noted that Hayflick’s methods involved establishing a huge bank of WI-38 and MRC-5 cells that, while not capable of infinitely replicating like immortal cell lines, will serve vaccine production needs for several decades in the future.

The vaccines below were developed using either the WI-38 or the MRC-5 cell strains.

- Hepatitis A vaccines [VAQTA/Merck, Havrix/GlaxoSmithKline, and part of Twinrix/GlaxoSmithKline]

- Rubella vaccine [MERUVAX II/Merck, part of MMR II/Merck, and ProQuad/Merck]

- Varicella (chickenpox) vaccine [Varivax/Merck, and part of ProQuad/Merck]

- Zoster (shingles) vaccine [Zostavax/Merck]

- Adenovirus Type 4 and Type 7 oral vaccine [Barr Labs] *

- Rabies vaccine [IMOVAX/Sanofi Pasteur] *

* Vaccine not routinely given

Researchers have estimated that vaccines made in WI-38 and its derivatives have prevented nearly 11 million deaths and prevented (or treated, in the example of rabies) 4.5 billion cases of disease.

Several vaccines currently available in the United States were developed using animal cell strains, primarily using cells from African green monkeys. These include vaccines against Japanese encephalitis, rotavirus, polio, and smallpox. Of these, only rotavirus and polio vaccines are routinely given.

Sources

- Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002.

- Barr Labs. (2011). Package Insert – Adenovirus Type 4 and Type 7 Vaccine, Live, Oral. (179 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome–United States, 1969-2004. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 54(11): 279–82. Accessed 01/10/2018.

- GlaxoSmithKline. (2011). Package Insert – Havrix. (123 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- GlaxoSmithKline. (2011). Package Insert – Hepatitis A Inactivated & Hepatitis B (Recombinant) Vaccine. (332 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Hayflick, L., Moorhead, P.S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Experimental Cell Research. 1961; 25(3):585. Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Hayflick, L. Personal correspondence. April 2017.

- Hayflick, L., Plotkin, S.A., Norton, T.W., Koprowski, H. Preparation of poliovirus vaccines in a human fetal diploid cell strain. Am J Hyg. 1962 Mar;75:240-58.

- Lindquist, J.M., Plotkin, S.A., Shaw, L., Gilden, R.V., Williams, M.L. Congenital rubella syndrome as a systemic infection: studies of affected infants born in Philadelphia, USA. Br Med J 1965;2:1401-6.

- Merck & Co, Inc. (2009). Package Insert – Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Virus Vaccine Live. (196 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Merck & Co, Inc. (2006). Package Insert – MERUVAX II. (88.6 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Merck & Co, Inc. (2010). Package Insert – Refrigerator-Stable Formulation – ProQuad. (448 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Merck & Co, Inc. (2017). Package Insert — Rotateq. (88.6 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Merck & Co, Inc. (2011). Package Insert – VAQTA – Hepatitis A Vaccine, Inactivated. (332 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Merck & Co, Inc. (2010). Package Insert – Varivax (Frozen). (220 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Merck & Co, Inc. (2011). Package Insert – Zostavax. (159 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- National Catholic Bioethics Center. (2019). FAQ on the Use of Vaccines. Accessed 11/10/2021.

- Olshansky, S.J., Hayflick, L. (2017). The role of the WI-38 cell strain in saving lives and reducing morbidity. AIMS Public Health; 4(2):137-148. Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Plotkin, S.A., Orenstein, W.A., Offit, P.A., eds. Vaccines. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008. Plotkin, S.A. The History of Rubella and Rubella Vaccination Leading to Elimination. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 43 (Supplement 3): S164-S168.

- Sanofi Pasteur. (2009). Package Insert – ACAM2000. (285 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Sanofi Pasteur. (2013). Package Insert – IMOVAX. (213 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Sanofi Pasteur. (2015). Package Insert – IPOL. (213 KB). Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Sgreccia, E. (2005). Statement from the Pontifical Academy for Life, including English translation of “Moral Reflections on Vaccines Prepared from Cells Derived from Aborted Human Foetuses.” Accessed 01/10/2018.

- Stanley Plotkin’s attenuated RA27/3 rubella virus vaccine was licensed in the United States in 1969 and is used exclusively in most countries. It is often combined with vaccines for measles and mumps in the MMR vaccine. Courtesy Stanley Plotkin, MD

Related

WHO Expert Advisory Committee on Developing Global Standards for Governance and Oversight of Human Genome Editing

REPORT OF THE SECOND MEETING Geneva, Switzerland, 26–28 August 2019

Convention on biological diversity, June 1992

Necessity

Cholera / R. Pollitzer ; with a chapter on world incidence, written in collaboration with S. Swaroop, and a chapter on problems in immunology and an annex, written in collaboration with W. Burrows

From Jared Kushner to Bill Gates to the corruption-riddled vaccine companies tied to the opioid epidemic to Silicon Valley tech giants and their role in martial law, rolling back civil liberties and authoritarianism — Whitney Webb unpacks the many conflicts of interests at play in the government and corporate response to COVID-19. She also discusses how the search for a cure ties into a larger agenda to use public fear over the pandemic to build a techno-tyrannical state worthy of George Orwell’s “1984.”

The connection between American eugenics and Nazi Germany, James Watson :: CSHL DNA Learning Center

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2800142/

Follow the Evidence.,,

Let the Corona Bubble burst!

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar